How did the human heart become associated with love? And how did it turn into the shape we know today?

As far back as the ancient Greeks, lyric poetry identified the heart with love in verbal conceits. Among the earliest known Greek examples, the poet Sappho agonized over her own “mad heart” quaking with love. She lived during the 7th century BC on the island of Lesbos surrounded by female disciples for whom she wrote passionate poems, now known only in fragments, like the following: Love shook my heart, Like the wind on the mountain Troubling the oak-trees.

Greek philosophers agreed, more or less, that the heart was linked to our strongest emotions, including love. Plato argued for the dominant role of the chest in love and in negative emotions of fear, anger, rage and pain. Aristotle expanded the role of the heart even further, granting it supremacy in all human processes.”

Among the ancient Romans, the association between the heart and love was commonplace. Venus, the goddess of love, was credited — or blamed — for setting hearts on fire with the aid of her son Cupid, whose darts aimed at the human heart were always overpowering.

In the ancient Roman city of Cyrene — near what is now Shahhat, Libya — the coin (above) was discovered. Dating back to 510-490 BC, it’s the oldest-known image of the heart shape. However, it’s what I call the non-heart heart, because it is stamped with the outline of the seed from the silphium plant, a now-extinct species of giant fennel. Why in the world would anyone have put that on a coin? Silphium was known for its contraceptive properties, and the ancient Libyans got rich from exporting it throughout the known world. They chose to honor it by putting it on a coin.

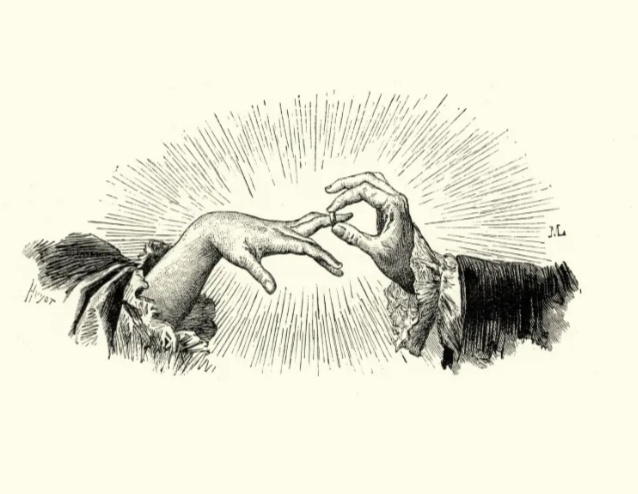

The ancient Romans held a curious belief about the heart — that there was a vein extending from the fourth finger of the left hand directly to the heart. They called it the vena amoris. Even though this idea was based upon incorrect knowledge of the human anatomy, it persisted. In the medieval period in Salisbury, England, during the church ceremony in the liturgy, the groom was told to place a ring on the bride’s fourth finger because of that vein. Wearing a wedding ring on that finger goes back all the way to the Romans.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, the heart found a home in the feudal courts of Europe. Minstrels in France celebrated a form of love that came to be known as “fin’ amor.” Fin’ amor is impossible to translate: today we call it courtly love, but its original meaning was closer to “extreme love,” “refined love” or “perfect love.” Courtly love required the troubadour to pledge his whole heart to only one woman, with the promise that he would be true to her forever. Accompanied by his lyre or harp, he’d sing his heart out in the presence of his lady and the members of the court to which she belonged.

This explosion of song and poetry that started in France spread to Spain, Portugal, Italy, Germany, Hungary and Scandinavia, each of which created its own variations. Through them, love staked out its place not only as a literary concept but also as an important social value and an intrinsic part of being human. A yearning for amorous love seeped into the Western consciousness and has remained there since. The illustration (above) is from the German Codex Manesse, a compilation of love poems which historians place sometime between 1300 to 1340. Between the couple, a fanciful tree rises to form the outline of a heart, which carries within it a coat of arms bearing the Latin word AMOR (love.)