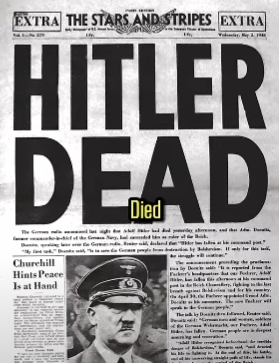

Winston Churchill visited the Reich Chancellery and bunker on 14 July 1945. On 11 December 1945, the Soviets allowed a limited investigation of the bunker grounds by the other Allied powers

Source :Toggle navigation

Articles

Prior to the Potsdam Conference with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in July 1945, President Harry Truman and Prime Minister Winston Churchill took separate tours of the nearby German capital. Wearing a lightweight military uniform against the heat, and accompanied by British military officials and his daughter Mary, Churchill visited the former Reich Chancellery, which had been Hitler’s official residence, office, and bunker.

Just before the war began, Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, had completed the New Reich Chancellery on the Volkstrasse, around the corner from the old. Intended to be the seat of Hitler’s government, it was a building designed to impress. Everything was on a massive scale, and Speer was given unlimited money to spend.

Churchill and his daughter wrote accounts of their tour on 16 July 1945. “The city was nothing but a chaos of ruins,” began Churchill. “No notice had of course been given of our visit and the streets had only the ordinary passers-by. In the square in front of the Chancellery there was however a considerable crowd,” he added in his war memoirs.1

“When I got out of the car and walked about among them, except for one old man who shook his head disapprovingly, they all began to cheer. My hate had died with their surrender and I was much moved by their demonstrations, and also by their haggard looks and threadbare clothes….Then we entered the Chancellery, and for quite a long time walked through its shattered galleries and halls.”2

Ronald McKie, reporting for the Argus newspaper in Melbourne, described the scene: “Inside the Chancellery Mr. Churchill climbed over heaps of rubble and rubbish, poked into rooms, wandered round the huge banquet hall, where two huge silver chandeliers had fallen to the floor. The smell of his cigar was strong and clean in the long ornate reception hall where Hitler once strode, and where field marshals once heiled.”3

Charles Moran, Churchill’s physician, and Field Marshal Alexander were also on hand. “In the Chancellery,” Moran wrote later, “the first room was carpeted a foot deep with papers and Iron Crosses, and there was Hitler’s upturned desk.”4

“Our Russian guides then took us to Hitler’s air-raid shelter,” Churchill continued. A flashlight lit their way to the concrete underground air-raid shelter. Stagnant water made the steps slippery. For Churchill, unsteady on his feet, the steps were precarious. Aided by his gold-headed walking stick, the Prime Minister made his way down the dark, wet steps but, with two flights yet to go, he thought better of it and slowly began climbing back to the surface.5

“Churchill emerged from Hitler’s bunker under his own power,” wrote Barbara Leaming, “but when at last he reached the top of the stairs and passed through the door of a concrete blockhouse into the daylight, his hulking frame appeared so shaky and depleted that a Russian soldier guarding the entrance reached out a hand to steady him.

“The Chancellery Garden was a chaos of shattered glass, pieces of timber, tangled metal and abandoned fire hoses. Craters from Russian shells pocked the ground. In one of those craters, Hitler and his wife had supposedly been buried after Nazi officers burned their corpses. The rusted cans for the gasoline still lay nearby. Russians pointed out the spot where the bodies had been incinerated. Churchill paused briefly before turning away in disgust.”6

Churchill rested on a beat-up chair that had been propped against a bullet-riddled wall. The Russians said it had been Hitler’s, Leaming continues:

Leave a Reply