Fascism is a complex and multifaceted ideology, but here’s a concise overview:

Core Characteristics

- Authoritarianism: Fascist regimes are typically ruled by a single powerful leader or group, with little tolerance for opposition or dissent.

- Nationalism: Fascism emphasizes the superiority of a particular nation, culture, or ethnic group, often at the expense of others.

- Totalitarianism: Fascist governments seek to control all aspects of society, including politics, economy, culture, and individual behavior.

- Suppression of dissent: Fascist regimes often use violence, intimidation, and censorship to silence opposition and maintain control.

- Militarism: Fascism often glorifies military power and aggression, using it as a means to expand territory, impose dominance, and suppress dissent.

Ideological Underpinnings

- Anti-liberalism: Fascism rejects liberal values such as democracy, individual freedom, and human rights.

- Anti-communism: Fascism opposes communism and socialism, often using this opposition to justify authoritarian measures.

- Racism and xenophobia: Fascist ideologies often rely on racist and xenophobic sentiments to mobilize support and justify aggression.

- Cult of personality: Fascist leaders often cultivate a cult of personality, presenting themselves as infallible and all-powerful.

Historical Examples

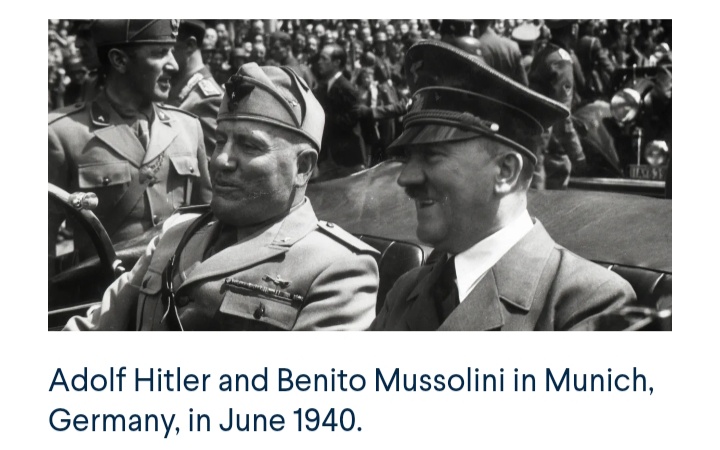

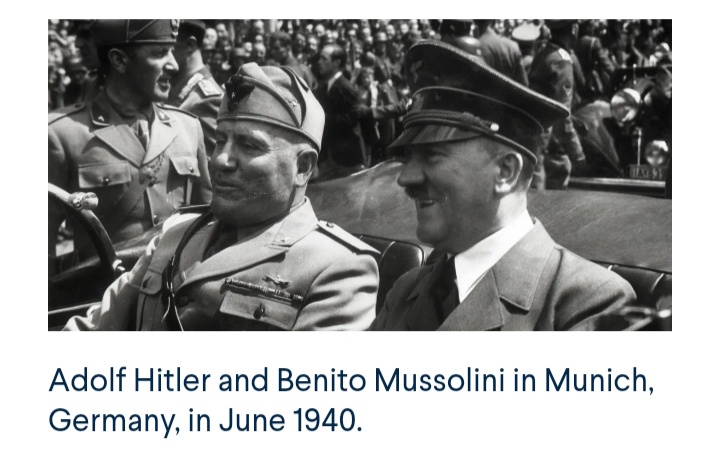

- Nazi Germany (1933-1945) under Adolf Hitler

- Fascist Italy (1922-1943) under Benito Mussolini

- Francoist Spain (1939-1975) under Francisco Franco

- Portugal under Salazar (1933-1968)

Warning Signs

- Erosion of democratic norms

- Rise of nationalist and xenophobic rhetoric

- Suppression of dissent and opposition

- Glorification of military power and aggression

- Cult of personality around a charismatic leader

Fascism is a complex and adaptable ideology that can manifest in different forms and contexts. Recognizing its characteristics and warning signs is crucial to preventing its rise and protecting democratic values.

Development in Eastern Europe

3 Fascism

There is very little agreement among scholars about the causes or social roots of fascism. Some argue that it is a form of psychological escape into irrationalism that is inherent in modernity. Others argue that it is the revenge of the middle and lower middle classes on the radical left, a sort of Marxism for idiots (Lipset 1963). Still others maintain that it is in fact a radical form of developmental dictatorship which appears quite regularly in late industrializing societies. Neither East European scholars nor British and North American specialists have been able to resolve the core disagreements on this question. Similarly, regarding fascism’s impact on Eastern Europe, economic historians continue to debate whether or not the German economic and trade offensive in Eastern Europe in the 1930s was a net gain or loss for Eastern Europe. In the short run, it appeared to have a positive effect, or at least was perceived to have had one among the East European elites. The design was a simple one and in some ways resembled the arrangements that the Soviets later instituted in the region. East European agricultural goods and raw materials would supply the German military industrial buildup. In return, the countries of the region received credits against which they could buy German industrial goods. Of course, in the long run these credits were all but worthless, and the onset of the war in the east ensured that the Nazis would never repay the debts they incurred in the 1930s. Yet the modest recovery of the East European economies during the early Nazi years could not help but to draw these countries more firmly into the Nazi sphere of influence.

The hope of many regional elites was that Germany and Italy would accept their Eastern neighbors as junior partners as long as their institutional and legal orders mirrored those of the masters.

Thus, in Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Estonia, local Hitlers and Mussolinis came to power in the 1930s, and even where they did not come to power they waited in the wings for the day when German or Italian armies would install them at the top of the political pyramid. Of course, the ideological design of the right and its subsequent institutional expressions were far less elaborate or well articulated than the liberal one. This was so not only because it was much newer, but also because most ideologies of the right were explicitly antiprocedural and antiorganizational in nature. The ‘little dictators’ of Eastern Europe did not, for the most part, share Hitler’s racial fantasies, since Nazi ideology had little good to say about the non-Germanic peoples of the area, but they did use the opportunity to free themselves from parliamentary and other liberal restraints in pursuit of economic development and regional power.

As in the earlier liberal era, political elites corrupted the pure German or Italian model in an attempt to turn it to their own purposes. Nevertheless, the conflict between the fascist right, which favored a party dictatorship, and the technocratic right which favored a nonpolitical dictatorship was never fully resolved in any country of the region until the onset of the war in the east in 1939.

With the onset of World War II, the scales tilted in favor of the fascist right. An important indicator of these differences can be seen in minorities policies, especially with regard to the Jews. Anti-Jewish laws had been on the books in several countries of the region since the mid-1930s, and in some cases even earlier. By the late 1930s, often under German pressure, but sometimes voluntarily and with a good deal of enthusiasm, they were implemented in full force. It is nevertheless important to distinguish between the institutionalized discrimination of the 1930s and the historical ‘revenge’ against the Jews.